Point Energy Innovations

Where Tech Meets Real Estate: Perspective on an Internship at Point Energy Innovations

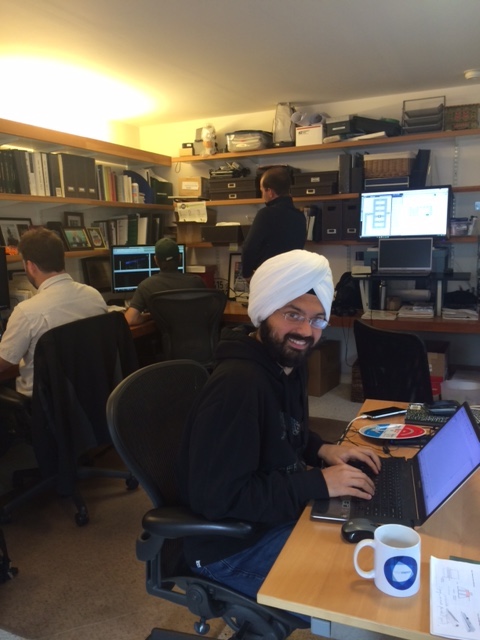

On 15, Sep 2015 | In PEI Blog | By Angad

By Angad Deep Singh

“Reimagining all things energy” embodies the vision I had when I decided to enter Stanford to pursue a Masters in Sustainable Design and Construction. While many of my fellow students were pursuing careers in tech, I hoped to take some of the innovative thinking the tech industry is known for and apply it to the slower moving world of real estate.

My Professor Peter Rumsey’s passion for applying unconventional thinking and innovative processes to achieve sustainability excited me more than anything else I’d heard at Stanford, so I decided to apply for an internship at his firm, Point Energy Innovations (PEI). It was an exciting ten weeks of learning, challenging every conventional design process and striving for continuous improvement in every aspect of design. Beyond energy and performance, I learned the importance of considering the legacy of a design on building inhabitants and how we can apply strategies from the fast moving tech sector to achieve remarkably superior buildings.

Point Energy gave me the opportunity to experience the sought after “startup life.” Agile and nimble in its approach, like most startups in the Silicon Valley, PEI allowed me to experience working in the “garage,” where Point Energy is headquartered. I was immediately struck by the energy and passion of the team in executing unconventional design. My first task was to analyze the need for insulating pipes carrying chilled water buried at a depth of two meters below the ground. We were concerned about the water gaining temperature as it flows from the cooling tower to the chillers.

Looking at soil characteristics (constitution, corrosive nature, heat transfer capability etc.) and rate of flow of water, we determined that even without insulation there wasn’t significant temperature gain but the corrosive nature required us to protect steel from coming in contact with the soil. Hence we decided to forgo insulation but coat the pipes with epoxy. In standard design, all buried pipes are automatically insulated. However, this is not always the best way to engineer a system. In this case, burying uninsulated pipes provided significant cost savings without impacting the performance of the system. This exercise provided me with the important insight that questioning rules of thumb in building design could save energy and materials and improve the quality of our buildings.

The built environment is one of the biggest contributors to the energy demand of any economy and hence also provides some of the largest opportunities for improving the energy efficiency. Creating highly insulated building envelopes with integrated passive design features such as maximizing daylight while minimizing direct sunlight and insulation for reducing power consumption for heating, cooling and ventilation ensures that the energy usage of the building is minimized while the needs and comfort of the building occupants are not compromised. These are essential features of every building that PEI designs. But there’s another unique concept that is an integral part of the design process at PEI. They call it “humanizing” building design.

Humanizing Building Design still remains an obscure concept to most building designers. I was able to comprehend the thought process behind this simple, yet extremely powerful phrase when I worked on designing a Net Zero Energy middle school in Hillsborough, California. All classrooms in the building are naturally ventilated and cooled using outside air, with no mechanical cooling equipment. We implemented the strategy not only to reduce the energy consumption of the building but also to create a sense of ownership of the environment among the children in the school.

Incorporating the concept of environmental stewardship for the upcoming generation means that we help shape responsible citizens while at the same time making a school that uses minimal energy and boosts productivity of students. “Simplicity” and “inclusivity” are an essential and integral part of this concept. At each step of the design, we ensured that each stakeholder (occupants, maintenance staff, contractor, etc.) interacting with the building understood the intention behind our design and the purpose of the design, which would ensure that each aspect of the design is operated correctly maximizing results and achieving our target of creating an extremely comfortable yet low energy building.

Another obscure concept in building design, where “rules of thumb” and manufacturer claims still form the basis of design, is the practice of prototyping. Prototyping is a well-understood term in the technology industry, where various versions of the product are released and tested before the final product is released for use by the end consumer. A classic example of this is roof-top photovoltaic modules, wherein the design team often determines the number of modules to install based on the manufacturer’s efficiency claims. At PEI we were not satisfied with going purely by claims of the manufacturer and decided to adopt the “prototyping” approach. While designing buildings for a large well-known technology company in Silicon Valley that included building integrated photovoltaic modules, PEI decided to set-up a field experiment to determine the average efficiency of the module, while also determining how various environmental factors impacted the module efficiency. The results will allow building designers to more accurately predict the number of modules needed, resulting in better building design.

Although, the construction industry remains a traditional space with little acceptance of newer ways of doing things or outlandish ideas, it provides an excellent avenue for innovators and ideators to revolutionize an industry that creates the very buildings we spend most of our time in. It was great to learn firsthand how Peter Rumsey along with the small but extremely passionate PEI team are acting as this essential catalyst of change.

Meet “The Father of Green Building”

On 07, May 2015 | In PEI Blog | By Molly

(Photo: Bisnow)

San Francisco’s Exploratorium is a place where kids learn about science through spectacularly fun interactive exhibits. It’s a place Point Energy Innovations founder, mechanical engineer Peter Rumsey, went to often as a child, and a place where he fell in love with science.

Embracing the curiosity and drive for experimentation the museum encourages, when the museum moved to its new location on Pier 15, Peter—while at Integral Group— led the design of the innovative bay water heating and cooling system, consulted on daylighting, and made many additional design decisions that helped the building to become the largest net zero energy targeted museum in the world.

The museum is about experimentation and innovation and the new design matches. San Francisco’s Bisnow recently toured the building with Peter. The Exploratorium and many of Peter’s other net zero energy designs led Bisnow to name him “the father of green building.” Learn more about the building and Peter’s approach to his work in this new Bisnow article.

What if Buildings and Companies Enhanced Ecosystems?

On 13, Apr 2015 | In PEI Blog | By Alexis

By Alexis Karolides

What if building codes actually required new projects to enhance a certain number of ecosystem services — such as sequestering carbon, building topsoil, enhancing pollination, increasing biodiversity or purifying water and air?

Is it possible that a city could be functionally indistinguishable from the wild landscape around it? And what if companies ultimately built factories that truly enhanced ecosystem services?

These were the big questions that biologist and biomimicry expert Janine Benyus posed during her keynote presentation at the recent International Living Future Institute’s 2015 unConference in Seattle.

To help unlock the potential answers to such questions, Benyus introduced the phrase, “the adjacent possible,” or the evolutionary process that causes species to adapt to changes while allowing adjacent evolutions to become possible.

“Don’t try to figure out what you did today, but what you made possible today,” Benyus said.

That high-level guidance followed a more concrete example of the potential to bridge urban design projects and ecosystem services: Sarah Bergmann’s description of creating the Pollinator Pathway, a plan to strengthen and reconnect fragmented landscapes, merging ecology, design and planning.

The first project, Pollinator Pathway One in Seattle, connects two distant units of landscape with new native ecosystems, boosting pollinators in the “connector gardens” from four species to over 1000 species. Importantly, the project also encouraged communities in-between to begin a conversation about bigger scale issues.

This project “made the adjacent possible” by connecting a fragmented landscape in the city, re-introducing pollinator species and involving people in creating and witnessing ecosystems in action.

A new design mentality

Imagine the unexpected benefits of providing nature in the city where the “nature deficit” is a silent but insidious drain on all of our well-being, and children’s well-being in particular.

Benyus referred to a University of California, Berkeley, study where students recorded their emotions throughout the day. The study found those students who felt “awe” more than three times a day had healthier levels of inflammatory proteins. (Unhealthy levels are correlated to autoimmune diseases and depression).

Nature is inherently awe-inspiring: soaring redwood forests, cascading waterfalls, emerald green hills after spring rains. But we can also be inspired by other people, and this, too, can make the adjacent possible.

Think of Interface carpet founder Ray Anderson reading Paul Hawken’s book, The Ecology of Commerce, and then transforming his company to become a global leader in sustainability.

But how do those of us honing green designs make “the adjacent” possible? How can our building projects, cities, and companies provide “positive externalities,” or side benefits?

Amory Lovins likes to say, “We know it’s possible, because it exists.” But sometimes people need to really be introduced to what is possible.

In considering these larger questions, I thought back on one example from my days at Rocky Mountain Institute, when I brought my current colleague at Point Energy Innovations, green buildings engineer Peter Rumsey (then leader of Rumsey Engineers), to a data center design charrette for EDS.

EDS had a capacity problem and was planning to invest huge assets in building new data centers, while existing data centers were gulping energy. We knew that retrofitting the fleet of existing data centers would be the big energy-savings “prize,” but the company wasn’t paying attention until we showed them what was possible in the design for a new data center they had planned for Wynyard, England.

Our design concept could function without chillers, making use of the favorable climate in Great Britain, with a combination of huge intake of outside air and cooling towers when needed.

When EDS saw that energy-slashing design, they hired us to create a global environmental strategy to retrofit the entire fleet of data centers and office buildings, which, it turned out, would save enough capacity to eliminate the imminent need to build all the new data centers.

Coincidentally, Hewlett-Packard acquired EDS at this time and we weren’t involved in implementing the strategy. Still, years later, former EDS client Dale Hoenshell told me that our design process had “changed the mentality of the whole company.”

Hewlett-Packard absorbed the new thinking and celebrated the stunning efficiency of the new Wynyard Data Center. They changed their industry status from a company targeted by environmentalists to a green leader.

Perhaps this, too, exemplifies what Benyus meant with the evolutionary metaphor; it took a sequence of design steps, engagement, inspiration and the hard work of people who followed through and carried the torch. But all of that made the “adjacent possible.”

This blog post originally appeared in GreenBiz.